Introduction to Reading

Posted

I wrote in my last blog about how I started my school year.

I’d like to write this time about how I begin my classes on reading for the year.

I am often afraid that if our goal is to create lifelong readers (and learners) we often go about it all wrong. We bribe them with Accelerated Reader and Reading Counts, which sends the message reading is such a chore you must be rewarded for doing it. Read for the pizza! We make them answer endlessly dull textbook questions (which haven’t really gotten much better over the years in my view). We multiple-choice test them, which not only makes reading into chore, but implies that the writers of multiple choice tests are the infallible arbiters of the one correct interpretation of what students read. We hand them textbooks and computerized test-prep programs like i-Ready that make students cringe and want to run away screaming. (They’ve told me.)

When I think about it all, it’s a wonder any of our students want to read.

I do, however still think that reading texts together as a class matters. We get to rehearse what Jeff Wilhelm calls the “expert moves” readers make together. But more importantly, students can experience the power of words.

The power of words. Four simple words, but words we don’t include in any of our standards. We talk about the utility of words. Our standards talk about how to analyze different types of words. But no standards I have yet seen make it a priority to talk to students about the power of words, and how if we are not thinking deeply about what we read – we miss out on that transformative power. Words are how we think, how we perceive meaning, how we create the lenses through which we view reality.

Since my goal is to teach The Power of Words 101, my first day of reading is a bit packed.

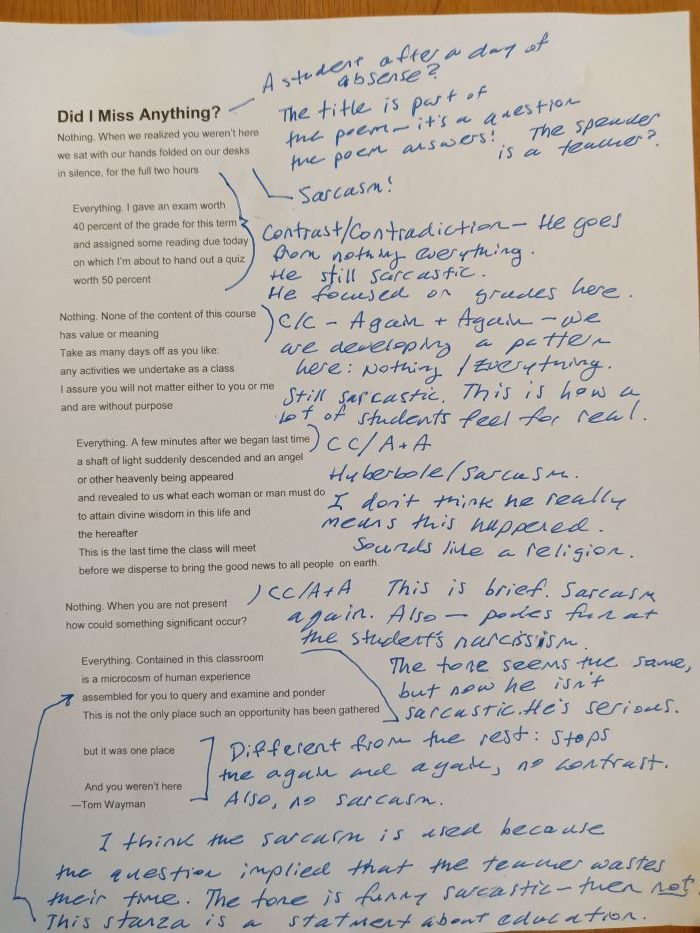

First, I hand them Tom Wayman’s poem “Did I Miss Anything?” I ask them to write down anything they are noticing and what they think it means. Go ahead and click on the link and read it now (or re-read it).

Many students are, frankly, baffled. I can tell a lot about their reading skills by what they notice and what meaning (if any) they find in the poem. Some students simply write IDK. This tells me a lot more about them than random guesses on a multiple choice diagnostic. Some try to interpret the poem, but get some fairly obvious features wrong (they think there are two speakers – one who says everything and one who says nothing). Some even miss that it is a teacher of some sort speaking.

But others get it. The note that the two speakers are divided between the title and main text of the poem – student and teacher. They get that the teacher is using alternating forms of sarcasm, and why. They get that the last full stanza is sincere.

I show them my annotations, and we discuss them:

We talk, at this point, about what matters more: the thoughts inside your head while you are reading, or how well you answer someone else’s questions about reading after you finish reading. They get it: what goes on in your head matters more (and even determines how well you answer the questions). In real life, what goes on in your head is all you will have left – there are seldom questions at the end in real life. We also talk about the meaning of the poem, and it is here that I introduce our Inquiry question for the year: What Is the Purpose of Education?

That final stanza, I tell them, is actually sincere. And it is what I try to achieve in my class: “Everything. Contained in this classroom/ is a microcosm of human experience/assembled for you to query and examine and ponder”. We talk about what a microcosm is. We talk about how we our class will be a place to query and examine and ponder. We will place texts, ideas, and questions in the center, and then examine them.

I then give them a list of Reading Process readers’ moves – things expert readers do: set purpose for reading, predict, visualize, etc. I have them check off the moves they tend to make already. We discuss them, and why they matter.

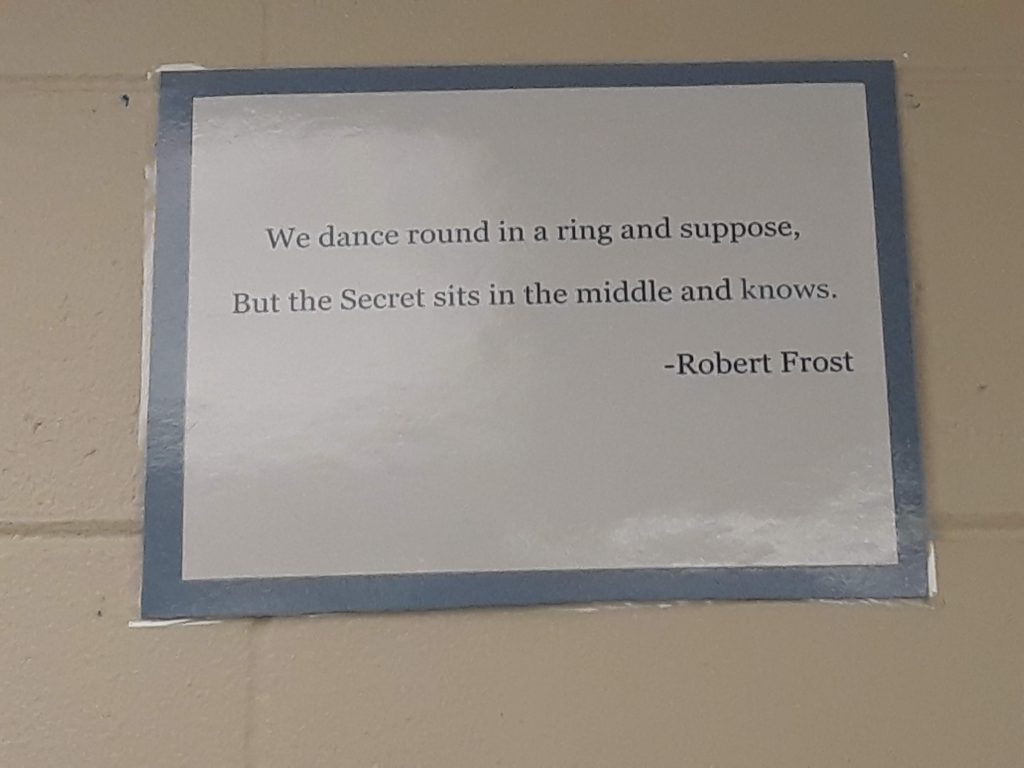

And then I give them the shortest text we will read all year – one I discovered in Parker J. Palmer’s book The Courage to Teach – Robert Frost’s “The Secret.” I ask them to jot down what they think it means. They do. They discuss their interpretations in small groups, then as a class. Invariably, it suddenly dawns on some of them – as we discuss whether the Secret is gossip or a literal secret someone is keeping, or God, or the meaning of life, or the secret to living well – that we are enacting the poem in class. The poem itself is the secret for us, in this moment. And we are each supposing we know what it is about. But only the poem itself knows, in a way. Robert Frost is dead. (I tell them I visited his grave when I was in high school – which I did!)

We then read a second poem, which I print on the same page: “The Blind Men and the Elephant.” I ask students to write down their thoughts and observations, including what they think the poem means and how it relates to the first poem. They do – and then discuss their answers in small groups, and then as a class.

Almost all of them see the pattern – people around a central object trying to figure it out and thinking their point of view is best. We talk about the importance of pattern recognition in life and at work. Students notice that this second poem is more detailed and complex. It’s almost like an essay, with an introduction and conclusion and six stanzas, like paragraphs, in the middle. They note that the blind men simply shout at each other. They don’t pool their resources and come up with a more comprehensive picture. They don’t switch places and try to experience the elephant a different way. They are all right in a way, but they all fail to see the big picture.

The takeaways from their brief discussions? The Elephant and the Secret might both represent reality – and we all like to think our perspective on it is the only right one. But maybe we need to realize we see only a part of the whole. They agree that both poems are sort of like our culture right now: everyone shouting everyone else down, full of certainty and unwilling to listen.

I tell them that the things we read all year will be Elephant/Secrets: we will place them in the center of the class, so to speak, and examine them. But unlike the blind men, we will share our ideas. The Purpose of Education is a Secret.

Have my students rehearsed expert readers’ moves and met standards? Yes. But they have gone beyond the standards.

Three simple poems can reframe our way of looking at reality, at the world around us, and at ourselves and our own limited, though often valid, perspectives.

That’s the power of words. Learning the power of words: That should be our main standard – our one standard to rule them all and in our classrooms bind them.

Apologies to J.R.R. Tolkien.

Above: I have Robert Frost’s poem front and center above my projection screen all year.