The Intellectual Bankruptcy of Education Reform

Posted

When school is in session in buildings, our students go to physical classes and… do what exactly? They often sit. They sometimes talk to the teacher and to each other. They do work of varying sorts. We call this learning. But what are they really learning? Are we really investing in their intellects, or has education as the powers that be have reformed it, become intellectually bankrupt?

Before starting to write this post, I looked up the term “Intellectual Bankruptcy” to see what would come up. People from both the left and the right have thrown it around – usually at each other. This, of course, strikes me as a kind of intellectual bankruptcy in and of itself.

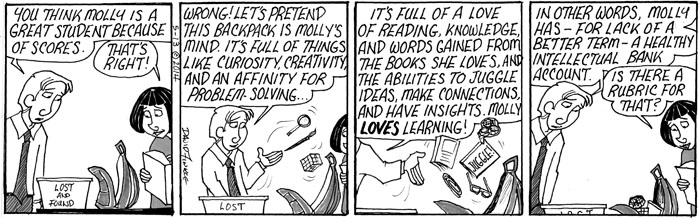

The idea that schools are no longer in the business of encouraging the growth of the intellect has been simmering in my mind for quite some time. In order to explain what I mean, I need to revisit a concept I actually visited in my comic strip some time ago: the Intellectual bank account.

In other words, the Intellectual Bank Account is not just knowledge, but the curiosity and drive to get more knowledge. The Intellectual Bank Account is about having habits of mind. Here are some of the habits of mind that make for a full bank account:

Curiosity. The desire to learn more, know more. It’s the desire to take things you already know and delve even deeper into them and to connect them to other subjects. As a child, I was fascinated by Disney Animation and by newspaper comics. My first forays into non-fiction reading were The Art of Walt Disney by Christopher Finch and Peanuts Jubilee by Charles Schulz. Both books took me deeper – they also taught me connections to other things I didn’t know were connected. I learned about Schulz’s influences – Krazy Kat, for instance. I learned that although animation started out as a fairly primitive art form, it developed rapidly into a craft that required extensive knowledge of life drawing, anatomy, and art history. Curiosity also leads you to ask questions about things you are learning.

Questioning may be the most important, and nuanced habit of mind. You need to understand how to generate questions, how to tell open-ended from closed-ended questions, how to know what questions are worth asking, and which questions lead nowhere. Questioning can be dangerous (as in questioning well-established science about how to save lives during a pandemic), but so can not questioning (as in not questioning the invisible internet filter bubble you live in). That is why it needs to be taught. And discussed. More on this habit in a later post. Defining good questioning and bad questioning – or whether the good/bad dichotomy even exists for questioning – is a matter of definition.

Knowing the importance of definition is another habit of mind. For one thing, whoever makes the definitions has the power. How do we define a citizen? How do we define a good or bad teacher? How do we define good writing? For another, our definitions shape our view of reality. What is patriotism? Blind obedience, or active questioning to make your country the best it can be? (See questioning above.) We need to be aware that the dictionary definition of words, especially powerful words, is only the most basic level of definition. There are nuances, built-up-histories, connotations, and personal histories with words that shade their meanings, and those meanings have real-world consequences. We have made the term “student achievement” synonymous with “standardized test scores.” That has had real-world consequences for over 20 years. (See below.)

As we walk through the world with our different definitions of the people, objects, and ideas that surround us, it’s important that we listen and try to understand each other’s points of view – to stand in each other’s shoes as Atticus Finch tells Scout. We should be able to imagine what it is like to be someone else, thinking their thoughts. This is the beginning of empathy, and it can happen when we debate, when we read fiction and non-fiction, when we learn history, or experiment in science. If I can’t try to imagine what it is like to be a student sitting in my class or on the opposite end of a computer chat – especially a student who is coming from a difficult home life for whom school is the last thing on his mind – then I am not the best teacher I could be. If I am leading a company and don’t care about the employees who get the job done each day, I may not be a very effective leader. I need to look at other points of view if I am a counselor, a minister, a politician, an architect, and author… a decent human being.

As we try to understand each other and the world around us, another habit of mind to practice is remembering that, as Marshall McLuhan posited and Neil Postman reiterated, the medium is the message. Take a message. Send it out to the world as a book, an article, a TV series, a movie, an Instagram post, a Tweet. It is not the same message in each of those forms, and it is good to remember that, especially when we are tempted to take in a diet of nothing but social media.

Of course, for all its toxicity, for all the ways it is abused, social media are not passive the way television was and mostly still is (the Kimmie Schmitt Choose Your Own Adventure notwithstanding). Another habit of mind is to be an active rather than passive thinker. It means not letting the world just wash over you all the time, but doing the things I’ve discussed above: being curious, questioning, defining, questioning definitions, trying to look at things from multiple perspectives.

Because, of course, another thing a healthy intellect is aware of is the importance of story. Story is a double edged sword – it can bring beautiful meaning into our lives, but it can also be used as propaganda. But we all see the world in terms of the story we think we are living – but we are so immersed in our own narratives, we are hardly aware of them. We need to be aware of our own stories – the stories we tell ourselves and the stories we live by. We need to be able to resist the stories that seem appealing on the surface but are hollow underneath. We once told ourselves the story that society would be better without so-called “morons” who were at the bottom of the genetic pool, so we started sterilizing people. The Eugenics movement inspired Hitler to take those ideas to their ultimate end. Narrative can kill. There are narratives killing people right now. The opposite narrative – that all men, all people were created equal – has been with us for over 200 years now, but we have yet to truly live up to the promise of that narrative.

We need to actively think to have a healthy intellect, and if you are an active thinker, it is likely you will become a creative thinker – an innovator. Creativity itself is hard to define, but it generally involves taking what you have learned from disparate sources and combining them into something new: an idea, a process, an invention, a work of art.

You may question the habits of mind I’ve listed here. You may want to add some. I probably will too by tomorrow. That’s good. But let’s just say my incomplete list represents something that we can mostly agree on. Does school, the way the education reformers has reconfigured it, promote a healthy intellectual bank account, healthy habits of mind?

Are teachers or students ever encouraged to question what is being done to them in the name of education reform?

Are students or teachers ever encouraged to consider the ways in which teaching and learning and student achievement have been redefined as “getting test scores”?

Are students or teachers ever encouraged to be curious as to who profits from these reforms – people like the testing and test prep companies (sometimes one and the same), the charter school operators, the virtual school CEOs the ed-tech companies?

Are students and teachers ever encouraged to think about the messages of the medium of standardized testing: That students are in school to be measured and sorted into achievement levels that help to solidify their futures for good or ill? That there is one right answer to every question?That answering questions is far more important than asking them?

Are students and teachers ever encouraged to think about the narratives that we use to run our education system? Here are some of those narratives: students won’t learn unless they are pressured with grades. Teachers are lazy and must be held accountable. The only way to tell how a school is “doing” is by administering standardized tests and using the results to grade and compare schools. Students’ socio-economic levels don’t matter if you can teach well enough. If it isn’t measurable it doesn’t matter. School choice, educational freedom, and the wisdom of the market place will solve all our educational problems.

Are teachers and students ever encouraged to question the prevailing ideas that are being shoved into our classrooms? We are told to use “best practices” like learning targets, rubrics, isolated standards, and reading instruction that discounts the inner life of the reader. Are we ever allowed to discuss these practices, or the idea of “best practices” itself?

Are students and teachers ever encouraged to innovate, to find new and better ways to do things in school? Are students and teachers ever encouraged to be active rather than passive about the what, why, and how of their education?

In case you haven’t figured it out, the answer to all those questions is No.

Which means that the system of education reform is promoting the opposite of healthy habits of mind. Instead of questioning and defining and being curious and actively learning, the system promotes passive acceptance. Instead of awareness, innovation, and open-mindedness, we have closed-minded compliance to whatever the system tells them to think and do. Instead of openness to possibility, we are teaching students to find the one right answer or lose points. We are encouraging binary thinking rather than complex, nuanced human thought.

Students are taught to write only in ways that will raise the scores produced by an algorithm. Students are taught to read like robots in order to mine for data and raise test scores and lose the real, human reasons to read.

And I firmly believe that this system has been perpetuated in part because it discourages the leaders coming up through the ranks to question anything that is happening. In fact, openly questioning what is happening probably would mean you would not get promoted at all.

The system is killing questioning, curiosity, and active learning. It is promoting passivity, dullness, and unquestioning compliance.

That’s what I mean by intellectually bankrupt.

What would you want for your own child? Investments in their intellectual bank accounts? Or the intellectual bankruptcy promoted by a standardized, top down, compliance-driven system of education that values all the wrong things?

I suspect I know the answer.