Black Stories Matter

Posted

In this cultural moment, which has lingered longer than might have been expected in our short attention-span culture, I was unsure how to address the issue of persistent racism and police violence against blacks in our society. I draw a comic strip. I am a middle aged white guy. But I have taught students of all races for 28 years. I have black colleagues and I have worked for black administrators. Still, my fear was that I would trivialize the subject.

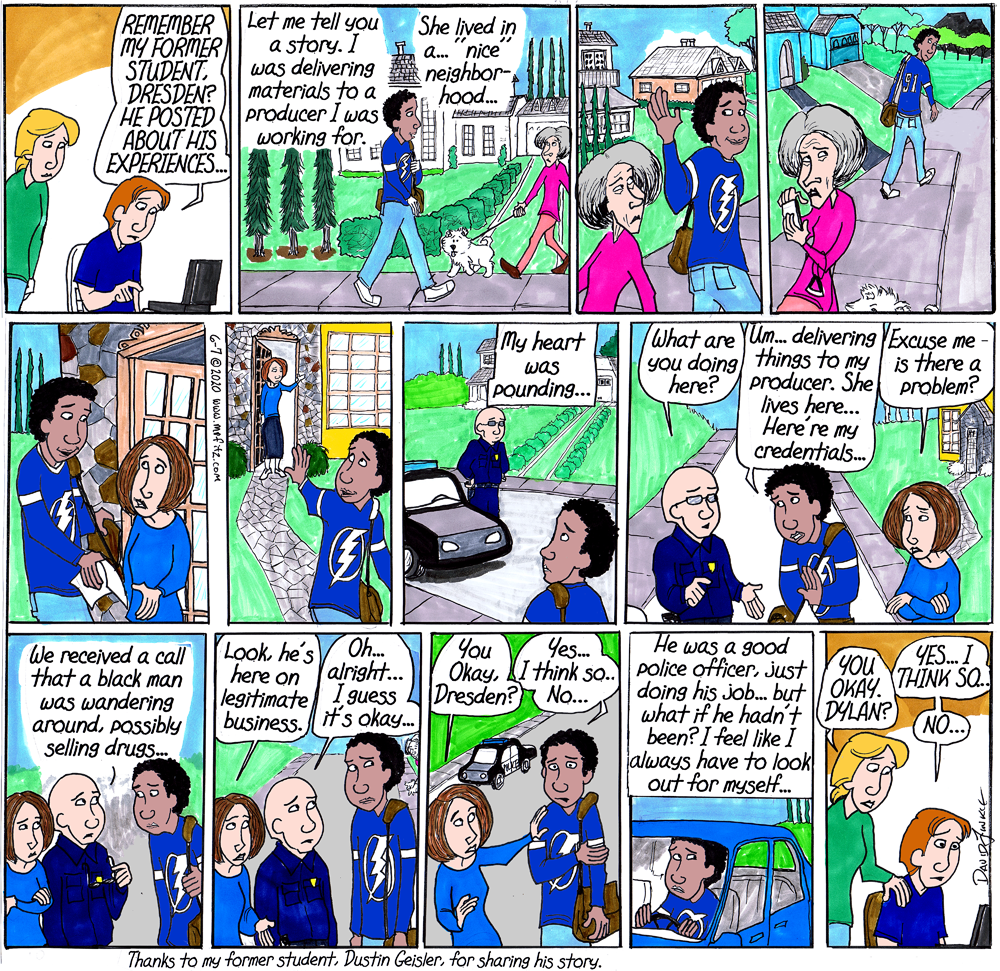

Two things appeared on my social media feeds nearly simultaneously (serendipity?) that gave me a way to speak up. I saw several posts that advised white people like me to sort of stand aside and elevate black voices. And then I saw a post by a former student, Dustin Geisler, about being on the job as a production assistant in California and having a white woman call the police on him just for being in the neighborhood. Dustin is one of my very favorite former students. He works for Disney, and for a long while he worked at Disney’s Hollywood Studios at Walt Disney World at a now-replaced attraction called The Great Movie Ride.

At one point, my own kids and I were entering the Grauman’s Chinese Theater replica the ride is housed in, and we were greeted by a very tall man in an usher’s uniform. He nodded and waved at us, and I thought he looked familiar. A few minutes later, when we were on the ride car, I heard a voice say, “Excuse me – are you a teacher?” Dustin had been our greeter as we entered, and he had recognized me. We had a quick chat and then the ride was on its way, but it put us back in touch.

Some time later, Dustin got cast as a gangster in the 1920’s mob thriller room of The Great Movie Ride. The role he played involved ousting the Disney tour guide and taking over our car. Even from the back of our large ride car, I could tell it was Dustin in that zoot suit and fedora, speaking in that gangland accent. I wasn’t sure he had seen me, though. When our car arrived in the Indiana Jones room so that gangster could meet his untimely end stealing a forbidden stone from a temple, Dustin got off the car and as he walked past us gave me the “I am watching you” – two fingers pointing at his eyes and then pointing at me. He had indeed recognized me. You don’t get moments like that in any other profession. Only in teaching.

When Dustin posted his story, the fact that a person as authentically wonderful, enthusiastic, and kind as Dustin could be profiled this way moved me immediately. And I knew he had provided me with a way to speak up. We messaged back and forth a bit. He agreed that telling his story as a comic would be a different and effective way to tell his story. I typed up a script and sent it to him. When he replied, he admitted just the script had made him cry a little. Which made me cry a little. When you know people you care about are being treated badly, it saddens and enrages you.

I drew the strip, consulting with him about what he wanted on his character’s jersey, what his fictitious self should be called, and what the lady who called the police looked like. We also went back and forth about a line in the strip that said the police officer was a “good police officer.” Ultimately, he agreed it was true to his impression at the time, but we both wondered how good he really was. Yes, he had to respond to the call, but he didn’t need to grill Dustin as much as he had. Some readers wondered what might have transpired if Dustin’s white producer had not intervened.

Here is the strip in its final form:

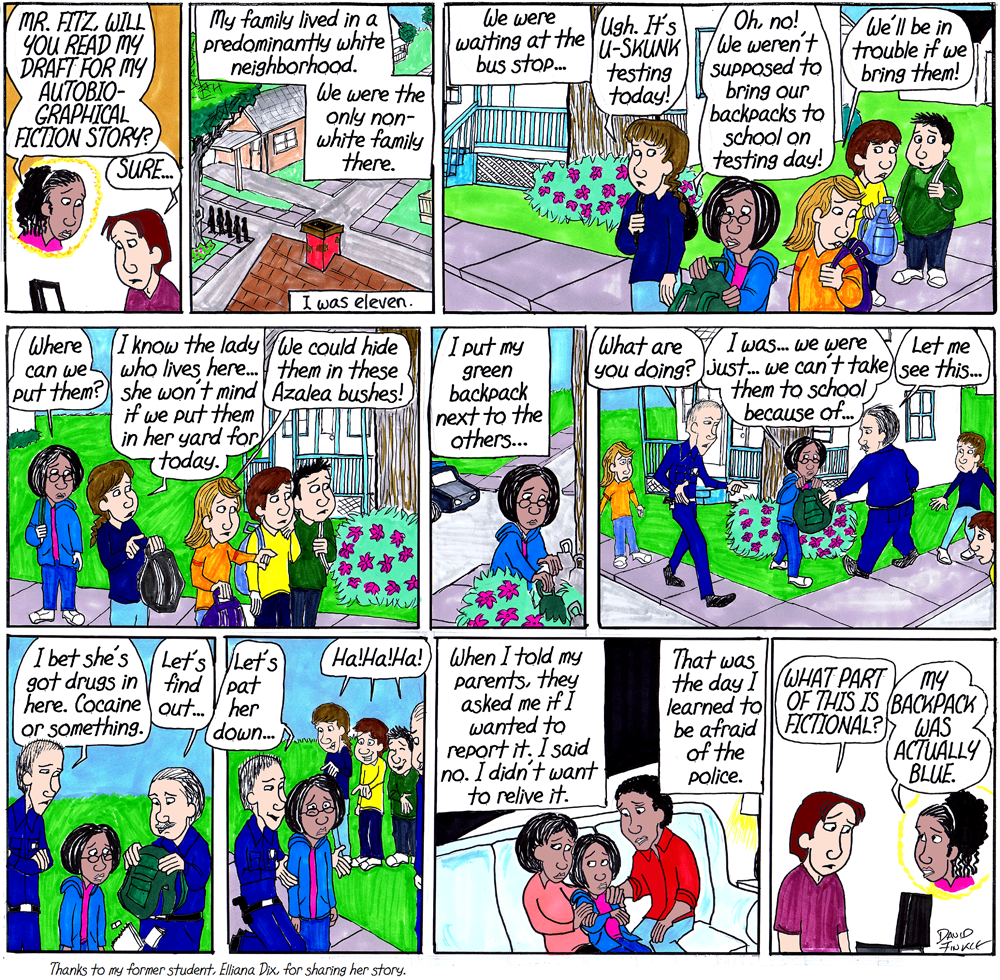

In the meantime, I wound up in contact with two other former students, Elliana and Lewis, a brother and sister who I taught for all three years of middle school as they looped with me through the Gifted program. Elliana’s story immediately grabbed me. It took place at a neighborhood intersection so close to my house that I pass it every night when my wife and I take our evening walk. And it wasn’t about a good police officer dealing with a phone call; it was police officers in my own town abusing their power at the expense of an 11 year old girl. As I read the report, I realized the story needed to be told – but it was hard to tell it. Hard to draw it. Hard to realize it had happened to Elliana while she was in my sixth grade class. As with Dustin’s story, Elliana and I collaborated and she had input on the strip.

Lewis, Elliana’s brother, recently told me another story – this one set at school and dealing with peer-on-peer racism. I haven’t quite figured out how to handle it in the strip yet.

Dustin and Elliana and Lewis all told me their stories. Here’s the thing: they all told their stories well: eloquently, vividly, and unflinchingly. I haven’t asked them if my writing instruction so long ago had any hand in that excellent storytelling. As I teacher, I can only hope it did. But here’s the thing: stories matter. And right now, in particular, black stories matter. But as I have pointed out fairly frequently, narrative writing is discouraged and nearly banned in schools despite its presence in the standards. Students are taught to write formulaically using text-evidence. Their own stories don’t matter. This winter, pre-pandemic I actually sat through a “best practices” workshop and was told our students don’t need to write all that well. All they need to do is “kick that text evidence back out and string it together. We don’t need their beautiful words.” The hell we don’t. They need to learn how to use their beautiful words. It’s a matter of life and death.

All three of these former students had one thing in common, despite their different stories. None of them spoke up or went outside their families about what had happened to them. There is a code of silence: don’t make waves, don’t speak up, don’t cause even more trouble.

I find myself wondering how many of my former students of color throughout the years have similar stories to tell. Probably all of them. I think about the students I just said goodbye to online at the end of this strange, pandemic-interrupted school year. How many of them have stories? I suspect I know the answer.

But school is devaluing story, ignoring narrative, because it isn’t tested. Add to that the code of silence that keeps people from speaking up, and it makes you realize how cellphones cameras have been a game changer. As teachers, we get tired of those devices, but they do have their uses.

I see the phrase “Equity Through Standards” thrown around online, as if standards are going to “level the playing field” for our minority students. But standards aren’t enough. A lot of things need to change, and not just in school. And where school is concerned, we need to be readying students for more than “college and careers.” We need to be getting them ready to participate in a democracy, and that may involve speaking up. Telling their stories. Speaking their truth.

Black stories matter.