Models for Education: Education as Synthesis (from 2017)

Posted

In my last post, I lamented the fact that our entire school system in the U.S. has been built around a model of assigning and assessing, of measurement. Everything we do in schools becomes about hoop jumping.

The Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus closed last night, though, so perhaps hoop jumping is too dated an analogy. My students have another metaphor. Regurgitation. We feed the knowledge to them, they puke it back up, and if it looks enough like what went down, they get a grade.

Disgusting, I know. But not that far off the mark.

As I begin to explore different models for how we might view education in this series of posts, I’m going to start here with a model I’m using in my class right now: a synthesis model.

Instead of asking students to simply regurgitate what we fed them, what if we, instead, asked them synthesize what they’re learning into something new and original? In his start-of-the-college-year address, “How to Think Like Shakespeare,” which I shared with my 9th graders this year, Scott L. Newstok introduces the idea of inventio, from which we get the words inventory and invention.

What if students weren’t learning things so that they can pass tests, but in order to synthesize them to invent something original? When I took Earth-Space Science in 11th grade, I learned about Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe, two warring astronomers, who held the fate of modern science in their hands. I’ve been working on a play about them on and off for the past 30 years, and may finally be getting into workable form! But over the years, I’ve read and learned a lot about them, their time period, and about science, not because I had to to pass a test. I learned about them because I wanted to use the learning to invent something.

Inventing something is almost always a process of synthesis. As Austin Kleon points out, to be creative you must “steal like an artist.” You borrow from here, and you borrow from there, you use things from your own experience, add some personal insights and some unusual connections… and you will arrive at something original.

For my ninth graders’ final exam in English this year, I am asking them to write an essay that answers the question, What is the purpose of education?

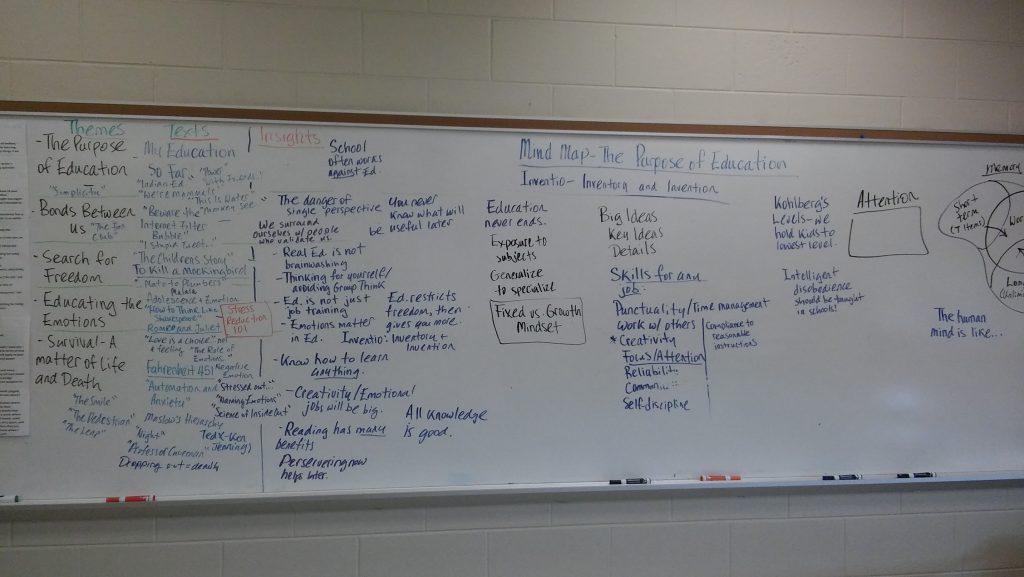

In getting them ready for this task, I have had them list in their notebooks all the unit themes we looked at, as many readings as they could remember, and as many take-aways as they could find, as well some fresh insights I supplied here at the end to tie things together. The result looked something like this on the board (and in their notebooks):

I have asked them to look beyond testing and grades to the deeper purposes of education. How does education influence our relationships and our democracy? How does education seem to restrict our freedom when we’re in school, yet become the key to our freedom when we get out into the world? What role should the emotions play in education? Is education a survival skill, and what kinds of education will help us survive an increasingly automated job market? Does education have purposes beyond “college and careers”? How does education help us build meaningful lives that go beyond mere survival?

I am asking my students to think creatively, to have original insights, to surprise me. I’m telling them to combine ideas from our class reading, and their own reading, with events from their own lives and insights of their own.

I have made it clear that I don’t want regurgitation.

I’m asking them, and anyone I can who works in education, “What would school look like if we stopped jumping through hoops and regurgitating and instead started building inventories of knowledge in order to invent things?”

Students could invent physical objects, insights, ideas, concepts, or works of art. And doing so would not only demonstrate their learning better than any standardized test can, it would develop one of the skills that can’t be automated and eliminated in the coming decades: creativity.