My Summer of Creative Teaching (from 8-20-11)

Posted

This summer I taught for the month of July. And I was blissfully happy. My wife, Andrea, and I tried having our own creative writing camp, which we called “Write Away!” It ran for two weeks (nine days, actually), and then I moved into the second half of my summer, teaching at the HATS Program at Stetson University, my alma mater.

I turned these experiences into a series of comic strips where Mr. Fitz taught a summer “Creativity Class.” I tried to capture some of the joy and fun that characterized all three of them. (I almost used the phrase “had in common” but then shuddered… “Common” has become a dirty word for some of us.) In any case, as I head into my 20th year in the public schools on Monday, I thought I’d reflect a bit on the summer, and on its contrast to what is happening to public education.

Our creative writing camp was inspired by a presentation at the National Council of Teachers of English by three teachers from Arkansas who had done a creative writing camp on a college campus there. After hearing about their model, we plotted our own version for months, joining forces with our friend Darlene, a children’s theater playwright and director, and searching for venues and trying to figure out how to make it work. We finally found a space in some classrooms at our own church, did a very little bit of advertising on Facebook, by word of mouth, and with a few posters. We got some actual sign-ups, and on the 5th of July we started our own camp with four campers, grades 5 through 8. By the end of the nine day camp, we had seven.

Each day began with a fun warm up that introduced the theme for the day. Our themes included Pirates, Space, Inventors, Nature, and Imaginary Creatures. Andrea had the first “period” of the day, poetry, and taught them that poetry is “words at play.” She got them playing around with words, exploring multiple genres.

I took the second section of the day, Fiction Writing. I taught them about the basic building blocks of writing fictional scenes– description, moment-by-moment narration, and dialogue. They wrote about pitch black planets, out of control vehicles, and aliens talking with humans. They tried their hand at story “grabbers,” and played around with basic premises. When we were brainstorming vehicles to write about being “out of control,” someone suggested the space shuttle crawler that moved the shuttle out to the launch pad at a very low rate of speed. I said a vehicle couldn’t be out of control at such a low speed. Our son, Christopher, who was assisting us, took that as a challenge, and managed to create a ten page long Cold War thriller about Soviet spies on the crawler trying to sabotage the launch. We had out of control lawn mowers and out of control canoes.

After a break for lunch, the writers moved to a larger room up the hall to work on play writing. They not only wrote, but learned about improvisation, creating dialogue in a different format, creating characters, and focusing a scene on a conflict.

After a quick walk around campus to clear our heads, our afternoon finished out with “free writing” time to finish any projects they’d worked on in the morning, or to try something original, in any of the three genres we’d worked in. The students were so conditioned to being told exactly what to write about and how to write it, this section of the day came as a bit of a shock to them. They were not used to being given autonomy, being given the chance to chart their own paths as writers. Eventually they got used to it, though, and settled in to write. Andrea and Darlene and I wrote too, along with the kids, and found we were enjoying and learning from each others’ lessons.

At the end of the first day, one of the students said, “I didn’t know writing could be this much fun!” How sad that by the end of 5th grade he had not experienced the fun of writing yet.

We ended the camp with a showcase where students shared their writing with their parents and grandparents, and then taught them some of the things they’d learned. We published an anthology of their writing at Lulu.com called Nine Days, Seven Kids, Pencils and Paper.

A good time was had by all.

The following Monday, the third week in July, I moved over to Stetson University for my third year of teaching a week long class called Flash Fiction. This class started in 2009 with five students, plus my son, Christopher. We spent two days working on the Close-Up aspects of fiction writing, narrative style, description, and dialogue , and on the “Long-Shot” aspects, such as plot structure, theme, irony, and character development.

We then spent all day Wednesday brainstorming a plot, using Chris Van Alsburg’s “The Mysteries of Harris Burdick” to spur ideas. We eventually cooked up a plot set in 1960’s Vermont concerning an ancient Native American tribe, a lake monster, and a ghost the plays the harp. Our outline included a two page back-story, a cast list, and a plot outline broken into chapters. We then divided up chapters on Thursday, and the last two days of the class were spent writing The Spirit of Lake Glimm. Seven people produced a novel in three days.

We repeated the process last year with seven students to come up with The Book of Arkavia, a classic fantasy world quest story in the spirit of The Wizard of Oz or The Chronicles of Narnia.

This summer we expanded to having thirteen student writers, grades 4 through 10, plus my son and myself, working on a book. Although we had gone through the process before, it was still a high-wire act: could we pull it off again, and could we pull it off with this many people? We thought about dividing into two groups and writing two different books, but that created it’s own set of problems. We spent Wednesday morning hashing out ideas based on the Harris Burdick pictures. We drifted toward another “collect the magical objects” story, then rejected it. We couldn’t settle on a focus. We went to lunch. We came back.

It was Wednesday afternoon, and we still didn’t even have a concept for our new novel. I was getting nervous, but I reassured the group by saying, “At some point, someone is going to have the idea, the idea that clicks all the other ideas into place, and everyone’s going to go, “Aaaaaaahhh!”

We decided to focus on the Harris Burdick drawings that took place in a house. Why were mysterious things happening in the house? Why was the pumpkin glowing? What was behind the secret door in the basement? Someone suggested that the things going on could be events from fairy tales. Someone else suggested a secret library of old books hidden in the basement. Christopher said, “What if the wall between reality and fiction is breaking down?”

And the class said, “Aaaaaaaahhhh!”

And we were off. We had talked all week about how everything in a story is there for a reason: to move the plot forward, to reveal character, to explore a theme, to create an irony, to foreshadow a later event or be payoff for earlier foreshadowing. We developed a list of characters and described them. We then made a list of fairy tales that could be invading the home of Jared and Paige Henry, our protagonists. We invented a back story concerning two secret societies, the Inklings and the Censors. It soon became clear that we would be touching on censorship and literacy issues, and that one of our themes would be the power of story to change lives. Everything in the story from that point on had to touch on that theme.

You need to picture this taking place in a computer lab. Everyone is sitting in chairs or pacing the room, watching the plot take shape in a Word document being projected on a big screen at the front of the room. I’ve heard some people say that today’s students need to change activities every ten to fifteen minutes. These students were completely immersed in plotting this novel for an entire day and a half. They were just talking and throwing out ideas and discussing what would work or not.

After we outlined and divided up chapters, we all began to write. Older writers helped younger ones flesh out their scenes. Kristine had to write a family dinner scene that turned into the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, so she looked up the original scene from Lewis Carroll online so she could emulate it in her version. I circulated, giving pointers and suggestions to students, one on one, on everything from style to formatting, to proofreading rules.

We worked through lunch to brainstorm a title and an idea for the cover. No one complained about working through lunch. They wanted to work! Students wanted to work. By Friday afternoon, students were finishing. We decided we needed a cover. Annie drew one, and other students decided to draw their own chapter illustrations.

They left, and over the next few weeks I edited the chapters into a coherent whole, ironing out plot inconsistencies that had crept in. We did not begin with a rubric. We did not begin with a multiple choice test. We began with the idea that we wanted to all write a story together and have fun doing it. (I’ll post the link to the book later, after the families have received their copies.)

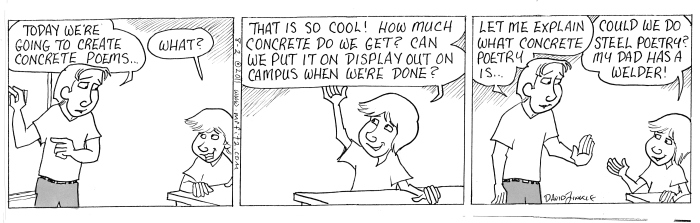

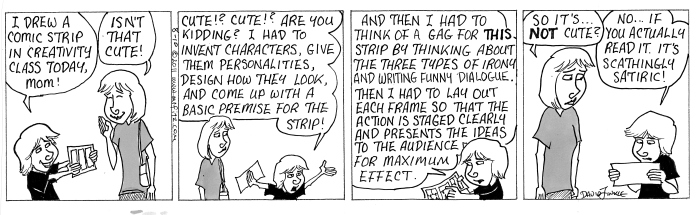

The following week was Cartoon Studio Class. The first part of the week was spent working on original comic strips. This may sound rather light-weight, intellectually. The big word in education right now is rigor. Well, how’s this for rigor? We discussed how to create a basic premise, types of irony, types of comedy, writing dialogue, how to frame shots cinematically, gesture drawing, the six basic emotions, how to design characters, how to stage action for clarity of ideas, and… well that’s not all. And that’s just comic strips.

Animation added a whole list of other concepts. We studied the history of animation, and worked with both hand drawn animation devices and with simple computer animation.

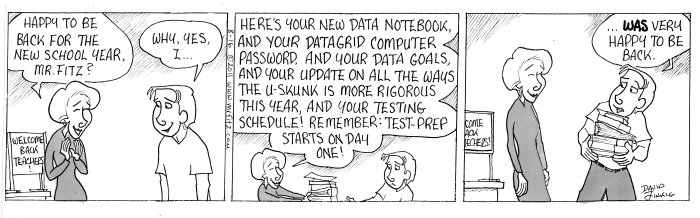

And again, no rubrics. No assessments. No “accountability” schemes.

One parent whose daughters attended both the Flash Fiction and the Cartoon Studio said that her girls came home exhausted every day, yet happy. She could tell their minds were being “stretched.” Rigor doesn’t have to mean making things difficult and unpleasant for the sake of making them difficult and unpleasant. Rigor doesn’t even seem like rigor if it’s done in the context of meaningful work.

Why did I enjoy this summer so much? Because, unlike the regular school year, where I must fill Yeats’s metaphorical pail, during this summer’s teaching experiences, I could instead focus on lighting his metaphorical fire instead. I had no standardized curriculum to follow. I could meet kids where they were at.

It was risky. I wasn’t sure what they would produce. I wasn’t sure if we would come up with good idea for a model. As Sir Ken Robinson says, creativity means being willing to risk failure. But when you are willing to risk it, you often find your successes are that much more valuable.

So as I head back to school Monday, despite the pressure to get students to perform on tests, despite the pressure to standardize both myself and my students, despite the experts who say creative writing isn’t rigorous, and the companies that demand we follow their programs with fidelity (which I’ve heard referred to as the new “F Word”), this year I will try to bring a little of this summer with me into the classroom. This year I will try to bring creativity, open-endedness, enthusiasm and joy of learning into my classroom.

And maybe I will allow myself to be blissfully happy again. No matter what anyone tries to say about it.