Why I Am Not Going To Use a Chatbot to Do My Writing For Me

Posted

Wendell Berry once wrote an essay titled “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer.” I don’t go as far as Wendell Berry – I am typing this essay on a computer – but on the other hand, I think he has some valid points. Even Stephen King has a section in his book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft about how writing by hand produces different writing than typing on a word processor. Information technologies change how we take in and produce knowledge and ideas. We read differently on most screens than we do on paper. Writing and thinking on paper differs from typing.

In the spirit of Wendell Berry, I am going to say that I am not going to use a chatbot to do my writing and thinking for me.

I’d been writing this post in my head for some weeks, but it became more urgent because of a response I got to this Facebook post that I posted earlier last night:

“Dear Microsoft and the Internet and various entities I see online: stop trying to cram AI writing down my throat. I have a mind and my own ideas and I will do my own writing, thank you. I love writing. Why would I outsource it to a stinking algorithm? (This post was written without the help of auto-text.)”

An anonymous teacher posted that I should “lean into” using the chatbots. When I replied that I would NEVER use a chatbot, the reply was “adapt or perish.” Um… fine. I’ll perish. But I’ll perish thinking my own thoughts and enjoying myself. Besides, does he or she mean that I will literally die for not using chatbots? That I will be left behind in the evolutionary development of the human race? That my writing will be overlooked and I will linger in obscurity because chatbot writing will be what sells in the future? (I’m already pretty content with my relative obscurity – I write for me these days.) That my students will not be employable if I don’t make them learn to prompt chatbots well?

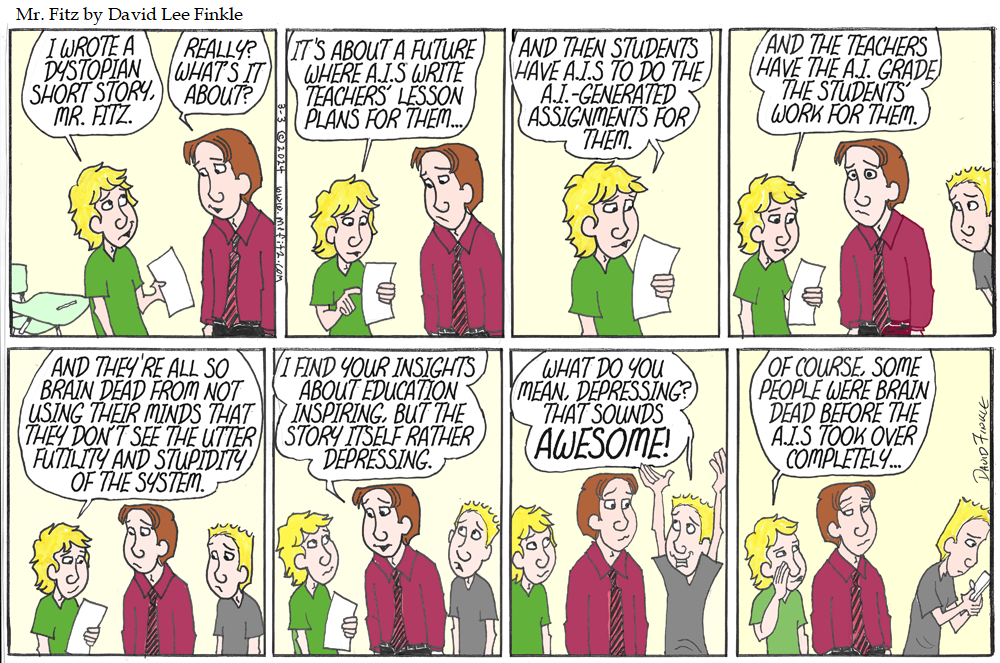

I’ve made three observations about people who are thrilled about chatbots doing their writing and thinking for them, which may or may not be true. One, people who are impressed by the output of the chatbots, it seems to me, never had a true appreciation for good writing in the first place – because everything I see being produced by bots is voiceless, bland drivel. Second, it seems to me that the kinds of writing we tend to focus on in schools are perfect for chatbots to write; these types of writing promote the idea that writing is a horrible chore to get through as soon as possible. Third, it seems to me that people who espouse using chatbots for writing don’t particularly like writing – which may not be their fault because of the way writing is often taught at school (see observation 2).

I mentioned earlier that the urge to write this piece became urgent last night. I am serious about that word: urge. And the urge is not to have a piece of writing over and done with. The urge is not for the product and it is not an urge to have someone or something else write ideas for me. The urge is to say something, to work through my thoughts, to produce word after word and idea after idea and arrange them and link them together. I have this urge frequently. It’s why I had to go back to producing comic strips two months after I left the newspaper. To paraphrase John Dewey, I don’t write because I have to say something; I write because I have something to say. I am currently reading a book called Why We Write: 20 Acclaimed Authors On How and Why They Do What They Do, edited by Meredith Maran. Not one of the authors mentioned writing to get it done and out of the way. They write about the urge to write, the need to say something, their love of the process, the way writing changes them as people. I try to help my students feel that same urge by giving them free choice of topics whenever possible, though the school system often has then focusing on having to say something.

Of course, I often don’t know what I have to say until I start writing. I discover what I think. I argue with myself. I hone my own intellect as I tinker with my thoughts and words. For me, writing is not just asking a robot to take ideas is finds online and combine them into something supposedly new. All art is, of course, derivative. But I “steal like an artist,” as Austin Kleon puts it, by pillaging my own lifetime of reading and viewing and filtering it through a lifetime of experience and thinking of my own. An algorithm pillaging the internet for ideas is not the same thing.

If we all hand over our writing to the chatbots, where will new ideas come from? In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury’s Professor Faber compares their dystopian society to the myth of Antaeus. Antaeus is the creature from Greek mythology who is powerful as long as it is touching the earth – once it’s held in the air, away from being “grounded,” it loses all its strength and is easy to defeat. In other words, when we are experiencing quality writing grounded in reality, it keeps us grounded, too, and stronger. The more our art is simply cannibalizing itself instead of drawing on reality, the less grounded we become. Chatbot writing has no real connection to reality. A chatbot has no real sensory experience to draw on. It is simply recycling ideas already in existence.

I have to question whether people who use chatbots actually like writing. Think of something you enjoy. Playing a game, playing a sport, solving puzzles, discussing the world with friends. Would you want to have a robot play for you, solve for you, discuss for you? Writing is, for me, about as much fun as I can have with my mind. I love all of it: getting the initial ideas, generating ideas, organizing ideas, inventing or finding just the right details, coming up with a plot, then inventing characters and letting them loose to wreak havoc on my carefully planned plot. I love thinking about writing when I’m not writing, for instance, while a mow the lawn. I love tinkering with sentences, finding just the right word, playing with paragraphing. It is all fun, and I wouldn’t want to miss a second of it.

Even if I could, I wouldn’t want a comic-strip-bot to produce and draw my comics for me. I love penciling the characters – choosing the settings, the staging, the facial expressions and poses. I love inking over the pencil lines to chose the best of all the sketchy lines to be the best one. I love erasing the pencil lines and seeing the final strip emerge. I love adding the color.

Here is where things get nuanced, however. I am not a complete Luddite. The current ethos seems to be, “If a technology is invented, you MUST use it,” or, as the anonymous person who commented on my post said, “adapt or die.” I certainly wish certain technologies had never been invented, and there are some I don’t use and some that I wish I didn’t have to use. (I avoid self-checkout at stores whenever possible; it seldom works for me, and I end up having to deal with a real person anyway, but now I am dealing with them in an annoyed state instead of a pleasant one. I’d rather have a human interaction in the first place.) It is the height of nonsense to say that you must use every technology that comes down the pike. Ask the Amish. For me, the nuance comes with my lettering. I have written every comic strip I have drawn for the past 24 years. But since 2015, I have NOT done my own lettering. I have typed up my strips and put them into my own font – the Fitz Font – and then set the margins to fit into bubbles, printed them, cut them out, and pasted them into frames. By the way, I don’t draw the frames every time I do a comic strip, either – I have tons of copies made so I can concentrate on the drawing itself.

Here’s the way I like to use technology: to do the less essential things so I can concentrate on what really matters and what I really enjoy. Drawing frames is mechanical, not creative. Lettering is time consuming, not creative. In the cases where lettering needs to be non-standard and creative – like when a character yells – I hand-letter it. The Fitz Font has enabled me to play larger parts in theater again, making possible roles like Harold Hill and Elwood P. Dowd. But the font does not write for me. The font is mechanical,not essential. Writing, for me, is essential, not mechanical.

Using a chatbot to write glosses over the process of writing to focus on the product. One of the many problems with how we use grades at school is that it focuses students (and teachers) too much on the product and not enough on the process. The process is where our thinking occurs, our learning occurs, our growth as people occurs. I journal every morning not to produce pages, but to dump my thoughts out and follow them down the page to see where they lead. Writing teaches me. Writing guides me. Writing helps shape who I am as a person. If I wasn’t writing, I would be a different person.

Of course, part of my personhood is that I like to create my own things. When I started drawing as a kid, other children would ask me to draw Scooby-Doo or Fred Flintstone. I told them that I only drew my own characters. One of my many objections to canned curricula is that I like to create my own curriculum, thank you very much. And I think I’m pretty good at it. I’m hearing about teachers letting chatbots write their lessons for them. No thanks. The chatbot cannot know my philosophy of education, my philosophy of what it means to be human, or my ideas about writing and reading. It does not know my students. Teaching, as Parker J. Palmer says in The Courage to Teach, is about more than technique. Good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher. I think good writing, too, comes from the identity and integrity of the writer. A chatbot is not a substitute for my identity, and so far as I know it is not capable of integrity.

I have seen the argument in several places that chatbots are just like calculators: everyone objected to them and now they are commonplace in math classrooms. I don’t teach math, so I can’t speak to this idea very well, but here is my thought: I think you can use a calculator to aid you in math and still come out of math classes with number sense, numerical thinking, and a sense for how to approach mathematical problems. I don’t necessarily see students using chatbots to write for them and having them come away with a real idea of how to write for themselves.

But the other idea I often see side-by-side with the calculator argument is this: chatbots and A.I.s are the wave of the future, so we must teach students how to use them or we are doing them a disservice. Perhaps, but this perspective smacks of technological totalism: again, if a technology exists you must use it. Resistance is futile, as the Borg on Star Trek would say. Actually, any number of technologies have been tried and found wanting over the course of history. Betamax, anyone? Some technologies have been outrageously successful and yet, over time, have proven to be incredibly destructive. Automobiles, for instance.

And I have yet to find a student writer who loved writing who used a chatbot. My students who have used chatbots usually hate writing. And using the chatbot didn’t make them love it any more.

Technological Totalism flies in to face of the idea of freedom. If we are not free to turn down technologies we do not wish to use, we are not really free. Can turning down certain forms of technology put you at a disadvantage in our society? Of course. But you can’t have a real yes unless there is the possibility of a no. Instead of unthinkingly plowing ahead, I wish we could stop and consider the implications of outsourcing our writing, our thinking, and our identities to algorithms we don’t really understand.

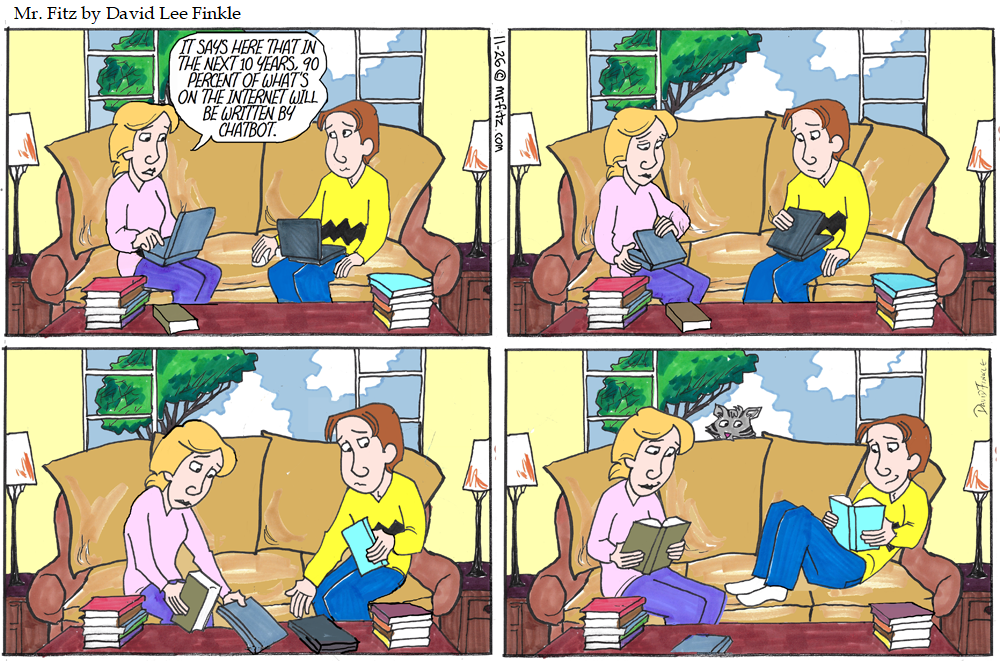

Chatbot writing subscribes to technology’s ethos of efficiency: fast is always good. But it’s not. Sometimes fast is just thoughtless, sloppy, and shallow. The best books I’ve ever read were not written efficiently; they were written through a long process of revision, rewriting, and thinking about what the author actually wanted to get a across. Writing and reading human endeavors – connections between people. When my wife recently read about the future of the internet, our response was pretty much like this:

In the Ken Liu short story “The Perfect Match” the protagonist is constantly advised by an A.I. named Tilly who talks in his ear through an earpiece, advising him about what to eat, what to wear, what to… everything. When he goes on a date, Tilly makes helpful suggestions about what to say to the girl across the table. He says what Tilly tells him to say in order to make a good impression… until he suddenly realizes the girls across the table is being advised by Tilly as well. She is saying what Tilly tells her to say to make a good impression on him. He realizes they are not actually having a human interaction, but instead are simply conduits for Tilly to talk to itself. He removes his earbud.

In his TEDx talk, “The Obsolete Know-It-All”, Ken Jennings, who is now the host of Jeopardy!, talks about losing a game of Jeopardy! to the supercomputer, Watson. He says that in the end, knowing stuff still matters. The things we know are part of what make us human. I would add to that that the thoughts we think and the thoughts we write down are part of what make us human. And when we give up doing that thinking and writing for ourselves, we forfeit some of our humanity.

In my classroom, I have a quote from George Orwell posted on the door: “If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.” We are now openly embracing not just letting other people do our thinking for us, but letting a machine do our thinking for us.

I write because I love to do it, because I have things to say, because I like to discover my own thoughts and hone them, and because I want control over how I express my thoughts. I write to have actual human interaction with my readers, not to be a conduit for what a technology has said for me. I will continue to do my own writing, and if there are occasionally errors in my writing, so be it. They help show that I’m human.